Transitional fossil

Transitional fossils (popularly termed missing links) are the fossilized remains of intermediary forms of life that illustrate an evolutionary transition. They can be identified by their retention of certain primitive (plesiomorphic) traits in comparison with their more derived relatives, as they are defined in the study of cladistics. Despite the limited nature of the fossil record numerous examples exist, including those of primates and early humans.

According to modern evolutionary synthesis, all populations of organisms are in transition. Therefore, a "transitional form" is a human construct of a selected form that vividly represents a particular evolutionary stage, as recognized in hindsight. Contemporary "transitional" forms may be called "living fossils", but on a cladogram representing the historical divergences of life-forms, a "transitional fossil" will represent an organism near the point where individual lineages (clades) diverge.

Contents |

Relation to the theory of evolution

| 1850 |  |

| 1900 |  |

| 1950 |  |

| 2002 |  |

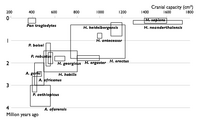

| These diagrams plot the set of Hominine species known to science as of a given year. Each species is plotted as a box showing the range of cranial capacities for specimens of that species, and the range of dates at which specimens appear in the fossil record. The sequence of diagrams shows how an apparent "missing link" or gap between species in the fossil record may become filled as more fossil discoveries are made. | |

In 1859, when Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species was first published, the fossil record was poorly known, and Darwin described the lack of transitional fossils as "the most obvious and gravest objection which can be urged against my theory", but explained it by the extreme imperfection of the geological record.[1] He noted the limited collections available at that time, but described the available information as showing patterns which followed from his theory of descent with modification through natural selection.[2] Indeed, Archaeopteryx was discovered just two years later, in 1861, and represents a classic transitional form between dinosaurs and birds. Many more transitional fossils have been discovered since then and it is now considered that there is abundant evidence of how all the major groups of animals are related, much of it in the form of transitional fossils.[3]

Examples

The reconstruction of the evolution of the horse and its relatives assembled by Othniel Charles Marsh from surviving fossils that form a single, consistently developing lineage with many "transitional" types, is often cited as a family tree. However, modern cladistics gives a different, multi-stemmed shrublike picture, with multiple innovations and many dead ends. Other specimens cited as transitional forms include the "walking whale" Ambulocetus, the recently-discovered lobe-finned fish Tiktaalik[4] and various hominids considered to be proto-humans.

Limitations of the fossil record

Not every transitional form appears in the fossil record because the fossil record is nowhere near complete. Organisms are only rarely preserved as fossils in the best of circumstances and only a fraction of such fossils have ever been discovered. The paleontologist Donald Prothero noted that this is illustrated by the fact that the total number of species of all kinds known through the fossil record was less than 5% of the number of known living species, which suggests that the number of species known through fossils must be less than 1% of all the species that have ever lived. Furthermore the fossil record is very uneven. Certain kinds of organisms, for example those without hard body parts like jellyfish and worms, are very poorly represented.[5]

Evolutionary taxonomy and cladistics

In evolutionary taxonomy, the prevailing form of taxonomy during much of the 20th century and still used in basal textbooks, taxa based on morphological similarity are often drawn as "bubbles" branching off from each other, forming evolutionary trees.[6] Transitional forms, are seen as falling between the various groups in term of anatomy, and are placed at the borders of these.

With the establishment of cladistic methods, relationships are now strictly expressed in so-called cladograms, illustrating the branching of the evolutionary lineages. The different so-called 'natural' or 'monophyletic' groups form nested units that do not overlap. Within cladistics there is thus no longer a transition between established groups, but a differentiation that occurs within groups, represented as a branching in the cladogram. In this context, transitional organisms can be conceptualized as representing early examples on the different branches of a cladogram, lying between a particular branching point and the "crown-group", i.e. the most-derived group, which is placed at the end of a lineage.

Transitional vs ancestral

A source of confusion is the concept that a transitional form between two different taxinomic group must be directly ancestral to one or both groups. This was exacerbated by the fact that one of the goals of evolutionary taxonomy was the attempt to identify taxa that were ancestral to other taxa. However, it is almost impossible to be sure that any form represented in the record is actually a direct ancestor of any other. In fact because evolution is a branching process that produces a complex bush pattern of related species rather than a linear process that produces a ladder like progression, and the incompleteness the fossil record, it is unlikely that any particular form represented in the fossil record is a direct ancestor of any other. Cladistics deemphasized the concept of one taxonmic group being an ancestor of another, and instead emphasizes the concept of identifying sister taxa that share a common ancestor with one another more recently than they do with other groups. There are a few exceptional cases, such as some marine plankton micro-fossils, where the fossil record is complete enough to suggest with confidence that certain fossils represent a population that was actually ancestral to another later population, but in general transitional fossils are considered to have features that illustrate the transitional anatomical features of actual common ancestors of different taxa rather than to be actual ancestors.[7]

Comparison to 'intermediate' forms

The terms 'transitional' and 'intermediate' are for the most part used as synonyms; however, a distinction between the two can be made:

- "Transitional" can be used for those forms that do not have a significant number of unique derived traits that the derived relative does not possess as well. In other words, a transitional organism is morphologically close to the actual common ancestor it shares with its more derived relative.

- "Intermediate" can be used for those forms that do have a large number of uniquely derived traits not connected to its derived relative.

According to this definition, Archaeopteryx, which does not show any derived traits that more derived birds do not possess as well, is transitional. In contrast, the platypus is intermediate because it retains certain reptilian traits no longer found in modern mammals and also possesses derived traits of a highly specialized aquatic animal.

Following this definition, all living organisms are in fact to be regarded as intermediate forms when they are compared to some other related life-form. Indeed there are many species alive today that can be considered to be transitional between two or more groups.

Missing links

A popular term used to designate transitional forms is "missing links". The term tends to be used in the popular media, but is avoided in the scientific press as it relates to the links in the great chain of being, a pre-evolutionary concept now abandoned. In reality, the discovery of more and more transitional fossils continues to add to knowledge of evolutionary transitions,[3][8] making many of the "missing links" missing no more (see List of transitional fossils)

The term "missing links" was used by Charles Lyell in a somewhat different way in his Elements of Geology of 1851, but was popularized in its present meaning by its appearance in Lyell's Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man of 1863, p. xi. By that time geologists had abandoned a literal Biblical account and it was generally thought that the end of the last glacial period marked the first appearance of humanity, a view Lyell's Elements presented. His Antiquity of Man drew on new findings to put the origin of human beings much further back in the deep geological past. Lyell's vivid writing fired the public imagination, inspiring Jules Verne's Journey to the Center of the Earth, and Louis Figuier's 1867 second edition of La Terre avant le déluge which included dramatic illustrations of savage men and women wearing animal skins and wielding stone axes, in place of the Garden of Eden shown in the 1863 edition.[9]

The idea of a "missing link" between humans and so-called "lower" animals remains lodged in the public imagination. The concept was fuelled by the discovery of Australopithecus africanus (Taung Child), Java Man, Homo erectus, Sinanthropus pekinensis (Peking Man) and other Hominina fossils.

Common arguments by creationists

Proponents of creationism have frequently made claims about the existence or implications of transitional fossils that paleontologists consider to be false,[10][11] and in some cases deliberately misleading.[12] Some of these claims include:

- 'There are no transitional fossils.' This is a claim made by groups like Answers in Genesis and the Institute for Creation Research.[3][13][14][10] Such claims may be based on a misunderstanding of the nature of what represents a transitional feature[13] but are also explained as a tactic actively employed by creationists seeking to distort or discredit evolutionary theory and has been called the "favorite lie" of creationists.[3] Some creationists dispute the lack of transitional forms.[15] .

- 'No fossils are found with partially functional features.'[16] Vestigial organs are common in whales (legs),[17] flightless birds (wings), snakes (pelvis and lung), and numerous structures in humans (the coccyx, plica semilunaris, and appendix).

- Henry M. Morris and other creationists have claimed that evolution predicts a continuous gradation in the fossil record, and have misrepresented the expected partial record as having "systematic gaps".[13] Due to the specialized and rare circumstances required for a biological structure to fossilize, only a very small percentage of all life-forms that ever have existed can be expected to be represented in discoveries and each represents only a snapshot of the process of evolution. The transition itself can only be illustrated and corroborated by transitional fossils, but it will never demonstrate an exact half-way point between clearly divergent forms.

- The theory of punctuated equilibrium developed by Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge and first presented in 1972[18] is often mistakenly drawn into the discussion of transitional fossils. This theory, however, pertains only to well-documented transitions within taxa or between closely related taxa over a geologically short period of time. These transitions, usually traceable in the same geological outcrop, often show small jumps in morphology between extended periods of morphological stability. To explain these jumps, Gould and Eldredge envisaged comparatively long periods of genetic stability separated by periods of rapid evolution. Gould made the following observation of creationist misuse of his work to deny the existence of transitional fossils:

"Since we proposed punctuated equilibria to explain trends, it is infuriating to be quoted again and again by creationists - whether through design or stupidity, I do not know — as admitting that the fossil record includes no transitional forms. The punctuations occur at the level of species; directional trends (on the staircase model) are rife at the higher level of transitions within major groups."—Stephen Jay Gould, The Panda's Thumb[19]

See also

- Evidence of common descent

- List of transitional fossils

Footnotes

- ↑ Darwin 1859, p. 279-280

- ↑ Darwin 1859, p. 341-343

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Prothero, D (2008-02-27). Evolution: What missing link?. New Scientist. pp. 35–40. http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg19726451.700-evolution-what-missing-link.html?full=true.

- ↑ Shubin, Neil (2008). Your Inner Fish. Pantheon. ISBN 9780375424472.

- ↑ Prothero 2007, pp. 50–53

- ↑ E.g. Bentons Vertebrate Palaeontology, 2nd edition, 1997

- ↑ Prothero 2007, pp. 133–135

- ↑ "Newly found fossils could link to human ancestor". CBC News. 8 April 2010. http://www.cbc.ca/technology/story/2010/04/08/tech-fossil-human-ancestor.html. Retrieved 2010-04-08. "It's tempting to call the new species a "missing link" between earlier species and modern humans, but scientists say the concept no longer applies, given new knowledge of human evolution. ... Researchers now say the evolution of humans consisted of a number of diverse species in many branches, not a single smooth line from ape-like species to humans."

- ↑ Browne 2002, pp. 130, 218, 515

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Lloyd, Robin (2009-02-11). "Fossils Reveal Truth About Darwin's Theory". LiveScience. http://www.livescience.com/animals/090211-transitional-fossils.html. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ Thompson, Tim. "On Creation Science and "Transitional Fossils"". http://www.tim-thompson.com/trans-fossils.html. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ Prothero 2007, pp. 126–127

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Isaak, M (2006-11-05). "Claim CC200: There are no transitional fossils.". TalkOrigins Archive. http://www.talkorigins.org/indexcc/CC/CC200.html. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- ↑ "The Scientific Case for Creation". Center for Scientific Creation. http://www.creationscience.com/onlinebook/LifeSciences27.html. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ↑ CMI: Arguments creationisats shouldn't use.

- ↑ Bergman, J (2000-08-01). "Do any vestigial organs exist in humans?". Answers in Genesis. http://www.answersingenesis.org/tj/v14/i2/vestigial.asp. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- ↑ "Evolution of Whales @ nationalgeographic.com". National Geographic Society. http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/data/2001/11/01/html/ft_20011101.4.html. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

- ↑ Eldredge N & Gould SJ (1972). "Punctuated equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism". In Schopf TJM. Models in paleobiology. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. pp. 82–115. ISBN 0-87735-325-5.

- ↑ Gould, Stephen (1980). The Panda's Thumb. New York: Norton. p. 189. ISBN 0393013804.

References

- Browne, E. Janet (2002). Charles Darwin: vol. 2 The Power of Place. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-7126-6837-3

- Darwin, Charles (1859). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (1st ed.). London: John Murray. http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=F373&viewtype=text&pageseq=1

- Prothero, Donald R. (2007). Evolution: What the Fossils Say and Why it Matters. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13962-5

External links

- Transitional vertebrate fossils FAQ, at the TalkOrigins Archive.

- Transitional species in insect evolution (discusses the evolution of termites from cockroaches, with particular focus on extant intermediate species).